What Happens After You Own the Care Plan

In Who Actually Owns the Care Plan in Autism?, the focus was on accountability—who ultimately bears responsibility when plans succeed, stall, or fail. That question does not end with the care plan. As providers evolve into care organizations, ownership expands beyond clinical intent and into system design, operational tradeoffs, and organizational risk.

This analysis uses a second-order systems lens: examining how well-intentioned care expansion creates indirect operational, incentive, and coordination risks at scale.

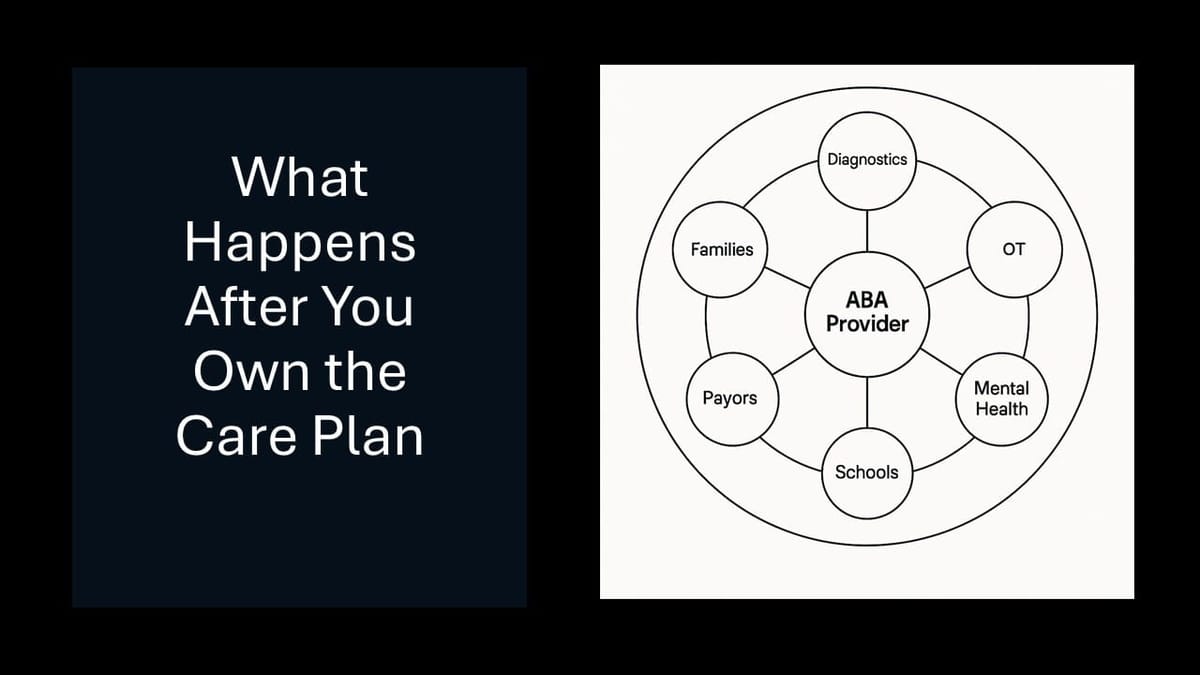

When ABA Providers Become Care Organizations

ABA providers are increasingly positioning themselves as care organizations, not just therapy vendors. Diagnostics, OT, ST, mental health services, school coordination, and case management are now framed as logical extensions of care—not strategic pivots.

That framing is directionally correct.

But it obscures a critical second-order reality:

As providers expand scope, they inherit coordination complexity without inheriting the infrastructure, authority, or reimbursement model required to support it.

Growth quietly becomes a risk transfer exercise.

The Second-Order Problem Being Created

Most expansion decisions are justified at the first order:

- Reduce care leakage

- Improve the family experience

- Capture more revenue per client

- Align with whole-child care narratives

What is rarely modeled is the second-order consequence:

Responsibility expands faster than control.

As scope increases, providers become the de facto integrator across:

- Diagnosticians with transactional incentives

- Therapists operating under discipline-specific norms

- Schools with independent mandates

- Families navigating fragmented systems

- Payors reimbursing services, not coordination

The organization absorbs the failure modes—without owning the system design.

What Changes at Organizational Maturity

At scale, the organization is no longer managed like a therapy business.

Clinical leadership becomes organizational leadership

Clinical decisions stop living exclusively inside treatment plans. They begin shaping staffing models, supervision ratios, scheduling logic, documentation burden, and family communication norms.

Clinical judgment becomes inseparable from operational governance.

Ops decisions start influencing care quality—indirectly

No one intends for operations to shape outcomes. It happens anyway.

Scheduling constraints influence continuity of care.

Productivity expectations shape supervision behavior.

Intake velocity impacts assessment fidelity.

Quality erosion rarely appears as a single failure. It emerges from optimized systems colliding.

Productivity metrics collide with cross-discipline reality

Metrics designed for single-discipline delivery strain under multi-service care.

Utilization targets distort supervision priorities.

Standard session assumptions break across OT, ST, and mental health.

Efficiency incentives quietly penalize collaboration.

What worked at smaller scale becomes misaligned at organizational scale.

Second-Order Effects Worth Naming Explicitly

These are not edge cases. They are structural outcomes.

Utilization targets distort supervision behavior

When supervision is both a clinical safeguard and a productivity lever, incentives drift. Oversight becomes transactional. Judgment compresses.

Intake optimization creates downstream scheduling fragility

Front-door efficiency assumes back-end elasticity. Most systems do not have it. The operation looks efficient—until it breaks.

“Comprehensive care” expands the surface area for failure

Each additional service line increases handoffs, documentation variance, coordination dependencies, and family expectation risk. Failure probability compounds, even as intent improves.

Technology sprawl becomes cultural debt

Point solutions solve local pain. At scale, they fragment accountability. Staff adapt through workarounds. Culture absorbs the friction technology was meant to remove.

The cost is paid in morale, not just software spend.

Why This Reframe Matters

This is not an argument against expansion.

It is an argument for honest modeling.

Reframing growth from capability expansion to risk expansion does three things:

- It challenges vendor “end-to-end” narratives that confuse integration with accountability

- It pressures PE assumptions that margins scale cleanly in coordination-heavy systems

- It questions the default belief that more services automatically produce better outcomes

Outcomes improve when accountability is clear—not when scope is broad.

The Quiet Truth

ABA providers scaling into care organizations are doing something genuinely hard—and necessary.

But the constraint is no longer clinical ambition.

It is organizational design.

The next generation of scale will not be defined by what services are offered, but by who truly owns coordination, decisions, and outcomes—and whether the system was built to carry that weight.

That is the second-order problem worth naming.

This post builds on the analytical frameworks used throughout ABA Mission, including second-order effects analysis and the distinction between clinical intent and organizational design.